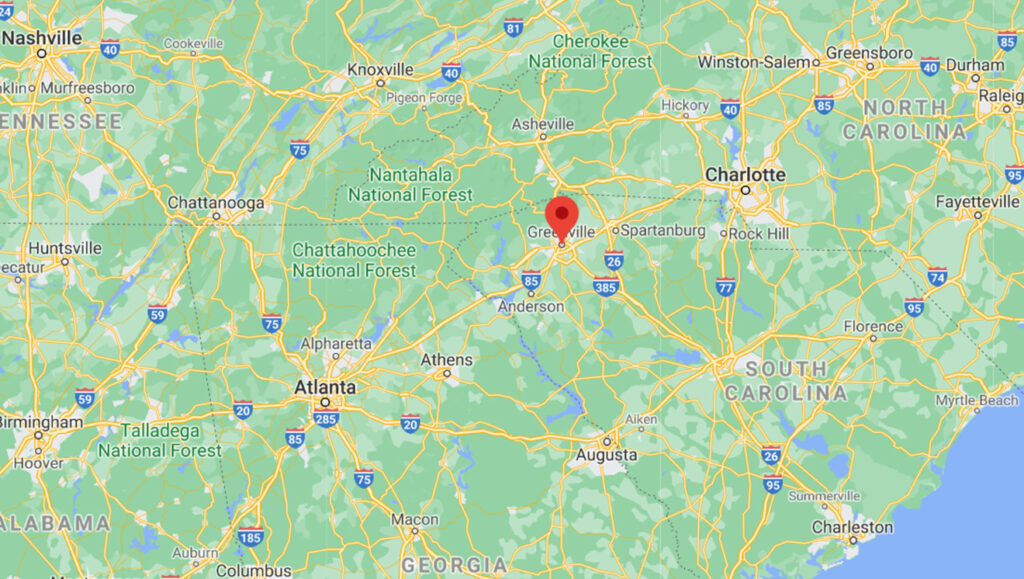

In 2018 I found myself in Greenville, South Carolina, for the first time. It was late afternoon and I was in town for a business meeting the following day. Tucked away in the northwest corner of the state in the foothills of the Blue Ridge mountains, surrounded by hundreds of miles of hiking and biking trails, the city of 70,000 is strategically located approximately two hours from both Charlotte and Atlanta.

After settling into an Airbnb, my colleagues and I decided to walk down to Main Street in downtown Greenville to explore the city and grab a bite to eat. As we walked along the historic tree-lined Main Street, I was surprised to find the area teeming with life. People were out and about on a Wednesday evening, outdoor cafes were full, and there was cuisine from all around the world. As we continued our walk we heard people speaking French, German, Spanish, Italian, and Mandarin. It’s something I’d grown used to in my native New York and my adopted hometown of Miami, where I’ve been living for the past 20 years, but South Carolina? This yankee was confused, albeit pleasantly surprised!

As we walked on the wide, shaded sidewalks we saw public art on virtually every block. There were construction cranes in the air. New, but thoughtfully designed, mixed-use infill projects could be seen sprouting up throughout downtown. I was perplexed. What was happening in Greenville?

We continued to walk south towards the Reedy River and came upon The Peace Center, where locals were lining up to watch a Broadway play. Just a few steps away the Reedy River Concert Series was in full effect. Hundreds of parents and their children were picnicking while listening to live music.

Intrigued, I went to bed that night determined to see more of Greenville, so the next morning I went for a run on the Swamp Rabbit Trail, a 22-mile multi-use greenway that runs along the Reedy River. Greenville was a mix of the great outdoors and vibrant street life. By the time I left town, I knew there was something special going on in Greenville — and I knew I had to return.

Fast forward to August 2020, with the pandemic in full effect. My family and I decided to take a summer road trip to Asheville, North Carolina, and later Greenville, South Carolina. Two years after I first set foot in the city, the south side of Main Street (known as the West End) was nearly unrecognizable. A number of mid-density apartments, condos, and hotels had sprung around the recently built 6,000-seat, minor-league baseball stadium, Fluor Field. New retail establishments and restaurants had also sprouted. Downtown Greenville was growing quickly — in a good way.

How Greenville Did It

After World War II Greenville’s economy grew like most cities, but during the 1960s and 1970s downtown Greenville fell into decline due to suburban migration. Luckily, Greenville had visionary leaders that believed in the city’s downtown. Mayor Max Heller (1971-1979) and Mayor Knox White (1995-current) were instrumental in helping and working with Greenville’s stakeholders to make downtown what it is today. They played the long game, and just recently Greenville was recognized as the #6 Best City in the U.S., according to Conde Nast Traveler’s 2020 Readers Choice Awards.

“Witty and charismatic, Max Heller was begged to run for mayor in 1973. He was so revered that he announced he would not seek a second term as mayor in 1975 unless business leaders did something about downtown’s decay.”

Reimagining Greenville

Austrian-born Max Heller moved to Greenville in 1938 to work for the Piedmont Shirt Company. The cotton mill industry was booming at the time, and Greenville had become the “Textile Capital of the World.” Heller worked his way up, eventually becoming vice president and general manager. He was asked to run for mayor in 1973, but he refused to seek a second term unless the business community supported and matched federal funding for the redevelopment of downtown. Soon after, the city received one of the first Urban Development Action grants ($7.4 million) and revenue sharing funds ($1.5 million).

Downtown business leaders respected and listened to Heller, and one of the first things he did was contract urban designer Lawerence Halprin, whose master plan called for widening sidewalks, minimizing driving lanes, and planting more trees. Suburban migration had resulted in an increase in crime downtown, and there were few businesses operating on Main Street. Halprin believed that planting shade trees and expanding sidewalks would be the first step in encouraging people to walk safely through downtown, which would in turn give business leaders the confidence to operate downtown.

“Cars are what drove customers, not sidewalks for people who never showed up. They clung to the hope that downtown would right itself on its own. But the major business leaders believed in Heller and, more importantly, supported him.”

Reimagining Greenville

By the time Heller passed the mayoral baton to Greenville native Knox White in 1995, a vision for the city had been cemented, and both men were determined to bring it to life.

“A vision was created that called for a different kind of downtown, one that Greenville and most of the nation had never seen before. A downtown where public art was key. Where housing was needed and promoted. Where anchors and building blocks were designed to draw people in and then lead them to the rest of downtown’s charms. Where retail shops were put on priority lists and underlined in red ink.”

Reimagining Greenville

How to Redevelop a Downtown Properly

One of the first large real estate development projects that reversed the blight of downtown was Greenville Commons, which opened its doors in 1982 right on Main Street. Surrounding the Hyatt Regency hotel, it included a five-story office building, a convention center, and a huge parking garage. Greenville Commons was significant because it was the start of public-private partnerships and it laid the groundwork for how the city would do business in the future. However, it would be years before Greenville would become known as the South’s best-kept secret. The Hyatt Regency lost money for 12 years. Success didn’t happen overnight, but there were 4 major projects during a ten-year span that helped change downtown Greenville’s character forever:

The Peace Center for Performing Arts

Greenville’s leadership wisely placed the Peace Center for Performing Arts on the banks of the Reedy River, just above Reedy Falls and on the southern, less developed end of Main Street. Opened in 1990, the center connected South Main Street and the Reedy River to the more developed north end of Main Street.

The funds to develop a large-scale performing arts center came from a unique private-public partnership that became a bedrock of Greenville’s redevelopment efforts. Greenville’s Peace family kicked off the fundraising efforts with a $10 million no-strings-attached donation. In 1989, a local arts advocate named Dorothy Hipp Gunter donated a Steinway Piano and $3 million to a 400-seat theater that now bears her name. Greenville’s school children raised funds to purchase a second Steinway piano. The city contributed an additional $6.4 million, the county $1.25 million, and the state $6 million. An astonishing 70 percent of the $42 million raised to build the Peace Center came from the private sector.

When the Peace Center for the Performing Arts opened, Alan Etheridge, executive director of the Metropolitan Arts Council, called it “one of Greenville’s biggest assets.” In addition to Broadway shows and plays, it’s home to the South Carolina Children’s Theater, the Greenville Symphony Orchestra, the Carolina Ballet and more. As Etheridge said, “Just look at what that facility has done for the community.”

The Redevelopment of the Historic Poinsett Hotel

Built in 1925, the twelve-story landmark hotel in downtown Greenville was one of the city’s first “skyscrapers.” Designed by New York City architect William Lee Soddart in the Beaux-Arts style, the hotel was developed in an era when small Southern cities demanded quality hotels to attract business travelers. In fact, the hotel in part was conceived to accommodate the biennial Southern Textile Exhibit, which attracted hundreds of attendees. The $1.5 million hotel was not an immediate success and lost money for the first five years. It managed to make it through the Great Depression and in 1946 was named the best medium-sized hotel in the nation.

By the time automobile ownership increased during the 1950s, downtown hotels began losing business to motels located near highways rather than in city centers. In 1959 the Poinsett was sold, but the new owners were unable to bring the hotel back to profitability and it eventually fell into such disrepair that the city closed it down in 1987. During the next 10 years the hotel was continually vandalized. Two fires were set to it. The Poinsett quickly became one of the most endangered historic structures in South Carolina.

Ten years later hotel developers picked it up and with the help of $4 million in tax dollars and Federal Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credits awarded as part of an almost $20 restoration, the Westin Poinsett reopened its doors in October of 2000. The hotel is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Construction of River Falls Park

With so many textile factories sprouting up along the Reedy River in the early twentieth century, locals started to refer to it as Rainbow Reedy due to the dyes used. The river looked bad and smelled worse. By the time city and state leaders erected a four lane bridge across the Reedy River Falls in 1960, the river itself was all but forgotten.

Then in the late 1960s the Greenville chapter of the Carolina Foothills Garden Club began weeding, gardening, and maintaining the area near the falls and below the bridge. Harriett Wyche, the president of the organization, called it “an oasis in the heart of the city” and referred to the bridge as the “concrete monster.”

With the help of the city, the Carolina Foothills Garden Club acquired roughly six acres of land around the falls from Furman College and several private landowners, and the Reedy River Falls Project was born.

“I was always drawn to the falls because of the history of the place. When I became mayor, it was the first place I would take visitors from out of town. You had to drive down to the river by a back alley and then go under the concrete bridge. I was impressed by their reaction, which was always strong. They would say, “Why in the world is this bridge here?” That confirmed for me that we had something special, though it was hidden away.”

Mayor Knox White

The Falls were located in what was known as downtown’s “West End” but was really just the southern end of Main Street. Back then this old warehouse district was seedy and blighted, and with the exception of the Greenville Army Store, no one dared to stop or linger. In an attempt to clean up the West End during the 1980s, many historic buildings were demolished and the area became a field of vacant lots.

With a shared belief that Falls Park could become the centerpiece of Greenville, Wyche and Mayor White teamed up to bring the area back to life. At the time the South Carolina Department of Transportation (SCDOT) owned the bridge. Elizabeth Mabry, the head of SCDOT, was active in a Columbia-area garden club. With that in common, Wyche reached out to Mabry and invited her to see the Reedy River Falls Project for herself. The idea proposed was that SCDOT would give the bridge back to the city with the understanding that the city would demolish it and redevelop the area under the bridge. According to White, “As soon as she saw it, Mabry became our biggest ally.”

Finally in February 2002 the city council voted to demolish the bridge and create a twenty-five acre park despite concerns over traffic. Once unveiled, the transformation of the Reedy River from a glorified sewer to Greenville’s masterpiece drew people from the north end of Main Street and served as the spark for the redevelopment for Greenville’s West End.

Fluor Field: Greenville’s Downtown Baseball Stadium

Greenville had a great history with professional baseball for almost seventy years before a Texas Rangers affiliate left in 1972 and the city’s Meadowbrook Field burned. In 1984 business leaders were able to reel in the Braves’ AA affiliate, but the team left in 2004 because the city would not meet the team financial demands for a new baseball stadium downtown.

When dozens of other teams began courting the city, Mayor White insisted that a new stadium downtown would include a strong mixed use component in keeping with the larger vision for downtown. Soon a Class-A Boston Red Rox affiliate called the Drive began calling Greenville home.

The team proposed building a six-thousand seat stadium near a private, mixed-use development on a city-owned nine-acre site in Greenville’s West End. The city provided the land, and since the Drive agreed to pay for the entire construction of the baseball stadium, monies that had been allocated by the city for the construction of the stadium were then used instead to invest in the emerging West End’s infrastructure.

Fluor Field opened on April 6, 2006 to a sold-out crowd. The team drew 330,000 fans during the first year, smashing the Braves’ previous record. Since then the stadium has become an anchor for the community. Bicycle road races begin and end at Fluor Field. College baseball games are played and other events are held there throughout the year as well. It’s become a beacon for the city, and a way to draw the community together. Today thIs once blighted area of downtown is teeming with apartment, retail and hotel construction.

“The saga of the baseball stadium was the longest and most controversial project the city had undertaken. There were enormous financial hurdles, lawsuits and little public support for the longest time for a baseball stadium downtown. But there was one constant- city council members who shared a conviction that downtown is where it belonged, and that made all the difference.”

Mayor Knox White

Mixed-Use Development

It’s also important to recognize that one of the main reasons downtown Greenville has succeeded, while many other downtowns languish, is the city’s commitment to encouraging the development of mixed-use projects in downtown Greenville. All of the projects stated above played an important role in Greenville’s transformation, however if it weren’t for the critical mass of mixed-use housing that the city incentivized developers to build, Greenville would not be experiencing the success it sees today. Without people living downtown and supporting the ground level retail and local businesses, Greenville’s downtown would probably look like many neglected downtowns throughout the country that never recovered from the suburban flight of the 60’s 70’s and 80’s.

Building a Local Economy

While Greenville’s economy was initially centered on textile manufacturing, favorable tax benefits have lured foreign companies to invest heavily in the area in recent decades. As a result, the region is home to the North American headquarters of Michelin, AVX Corporation, NCEES, Ameco, Southern Tide, Confluence Outdoor, Concentrix, JTEKT, Cleva North America, Hubbell Lighting, , Greenville Health System, and Scansource.

In 1992 BMW opened a manufacturing plant employing nearly 11,000 people in neighboring Greer. Ten years or so later, the Clemson University International Center for Automotive Research (CU-ICAR) was created, establishing CU-ICAR as the model for automotive research. The Center for Emerging Technologies in Mobility and Energy opened in 2011, hosting a number of companies in research and development and becoming the headquarters for Sage Automotive.

When Greenville’s Donaldson Air Force Base closed, the land became the South Carolina Technology and Aviation Center, home to a Lockheed Martin aircraft and logistics center, as well as facilities operated by 3M and Honeywell. General Electric also has gas turbine, aviation, and wind energy manufacturing operations in Greenville, and the city’s Donaldson Center Airport now occupies part of the former air base.

Transportation helps drive Greenville’s economic engine. Located on the Interstate 85 corridor approximately halfway between Atlanta and Charlotte, the city is served by a beautifully renovated international airport, Greenville- Spartanburg, a private aviation airport and an Amtrak station.

Greenville’s Future & Commercial Real Estate Development

Admittedly I haven’t spent much time in Greenville, but the little I’ve seen of the city has left a remarkable impression on me. There’s a lot to love about Greenville and it’s outdoorsy residents seem to enjoy a high quality of life. Its downtown is a place where people can live, work, and play because the city encouraged developers to build thoughtfully designed mixed-use projects from the very beginning.

Greenville stands to benefit from the macro-migration patterns in the Sun Belt states. There seems to be a young, entrepreneurial population that has moved to Greenville in recent years in search of a smaller city, better schools, and higher quality of life. I expect this trend to continue if Greenville’s future leaders and residents continue to reimagine how they can make Greenville more livable while attracting new businesses. This is a unique city that did things differently than other cities by investing in their downtown and should be used as an example for other cities. Greenville has what it takes to keep getting better and its redevelopment story seems to still be in the early innings.

Given the city’s commitment to sticking with their development plan to truly build a livable city where people can live, work and play it seems fair to reason that Greenville will likely see continued growth. Downtown Greenville has plenty of developable land still available and the city is in the midst of building a sixty acre park just west of downtown. Needless to say, Unity Park will likely become another catalyst to spur more development in Greenville and this will bring even more commercial real estate development opportunities to the city.

My wife and I have discussed the possibility of moving to Greenville in the not-so-distant future, but in the meantime, let’s not let the cat out of the bag. Please do not share this article until after we buy a home in Greenville. We don’t need more people moving there and driving up housing prices! Let’s keep Greenville our secret for now…